Haemophilus influenzae

Written for The International Microbiology Literacy Initiative

Claim to fame: mistaken identity

In 1892, the German physician and scientist Richard Pfeiffer isolated what he thought was the causative agent of influenza. He identified the small rod-shaped bacteria as Bacillus influenzae (Bacillus refers to the rod shape of the bacteria and influenzae refers to the disease he thought the bacterium caused.) Then came the 1918 flu pandemic, one of the deadliest pandemics in recorded history. In the frenzy of the outbreak, scientists and physicians were trying and failing to isolate the bacteria that Pfeiffer had originally identified from influenza patients. Many had ascribed their failures to poor technique, but a pair of scientists at the Rockefeller Institute suspected otherwise. Peter Olitsky and Frederick Gates collected nasal secretions from patients with influenza during the 1918 pandemic and passed those secretions through special filters that exclude bacteria based on size. They then took their filtered samples and found that, even after filtering out bacteria, the nasal secretions from influenza patients were still able to cause disease in rabbits, ruling out bacteria as the causative agent of influenza. Since then, the bacteria Pfeiffer originally identified as Bacillus influenzae has been renamed Haemophilus influenzae (Haemo- referring to the protein hemoglobin found in blood and -philus meaning beloved in Latin). This new name refers to bacteria that grow more robustly in the presence of hemoglobin, while “influenzae” was retained in reference to its original misidentification.

Resident Microbe

While H. influenzae is best known to us as a cause of illness, many adults and children are hosts of H. influenzae without even knowing it. Bacteria that reside on and within us without harming our health are described as “commensal,” so, although H. influenzae can cause disease, for most healthy individuals, H. influenzae is a part of the normal, commensal bacterial community. Over half of children are colonized with H. influenzae by the age of 6 and at least 75% of healthy adults carry a strain of the bacteria without issue. H. influenzae colonizes the mucosal lining in the upper respiratory tract of healthy individuals, primarily the nasal passages and the throat.

Opportunistic Pathogen

H. influenzae does not typically cause disease on its own; instead, it waits for the host to be afflicted by something else before causing problems. For example, a viral infection might weaken the immune system, which then allows H. influenzae to invade the lower respiratory tract, causing pneumonia. These types of pathogens are described as opportunistic because they only cause illness when other factors provide them with an opportunity. For this reason, those that are most susceptible to H. influenzae infection are those who are sick with a different infection, immunocompromised, or suffer from a chronic inflammatory disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

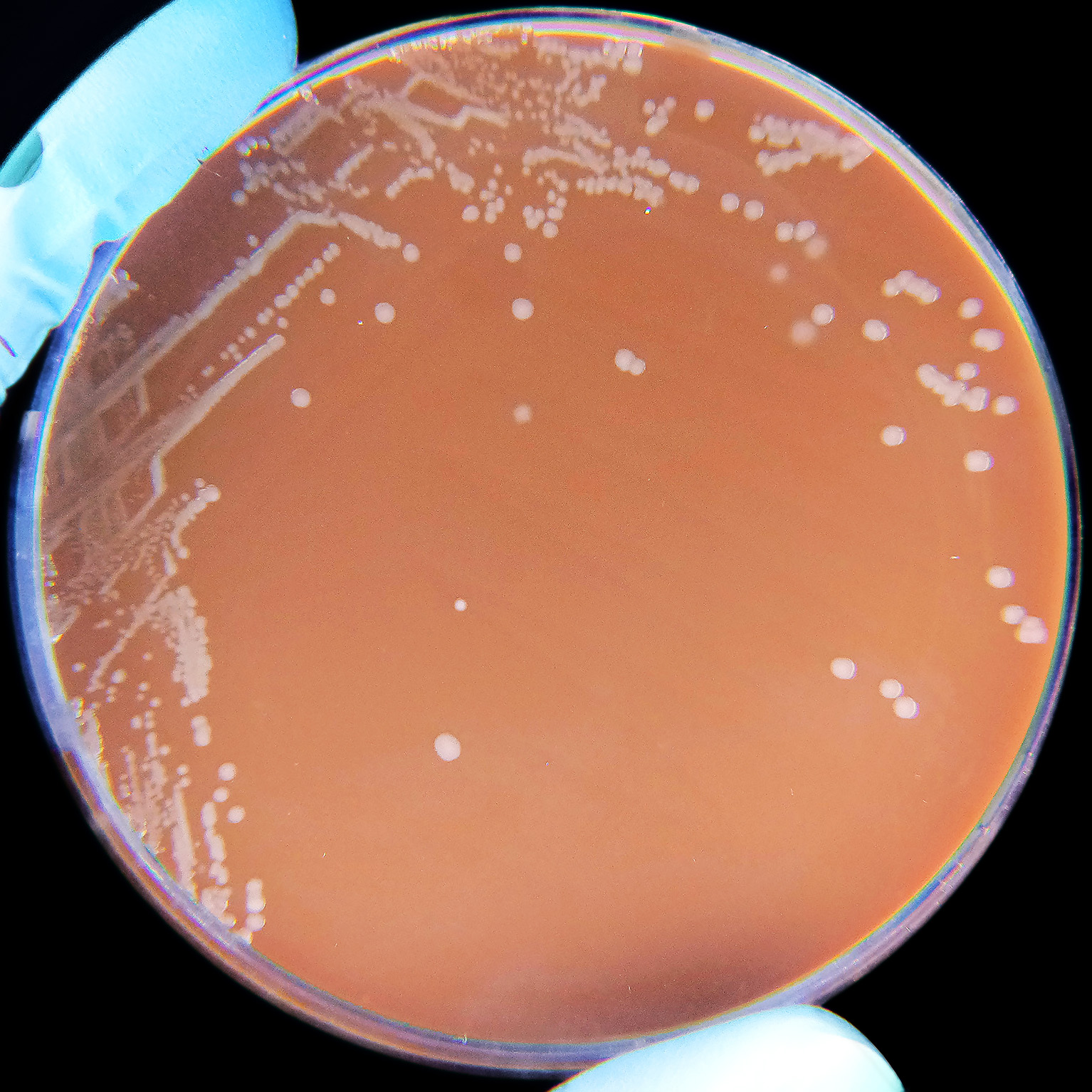

There are two main types of H. influenzae—encapsulated and unencapsulated. Encapsulated strains, the most prominent one being H. influenzae type b (Hib), have a coating surrounding its membrane. This coating protects the bacterium from being killed easily by our immune system. Hib causes a variety of different diseases depending on the location of infection. Pneumonia occurs when bacteria infect the lower respiratory tract; H. influenzae can also infect the membranes lining the brain and spinal cord, causing bacterial meningitis; and complications from both pneumonia and meningitis can cause bloodstream infections like bacteremia. Unencapsulated H. influenzae, on the other hand, lack the coating and are less pathogenic than encapsulated strains. Most commensal H. influenzae are unencapsulated; however, they still can cause disease. Unencapsulated H. influenzae strains most commonly cause nasal infections, ear infections, and eye infections.

Treatment

H. influenzae is particularly susceptible to the penicillin family of antibiotics, otherwise known as beta-lactams. The way these antibiotics work is by disrupting the machinery needed for the bacteria to construct their cell walls. However, H. influenzae can develop resistance to these antibiotics; the most common way is by acquiring genes that produce enzymes that are able to degrade these antibiotics called beta-lactamases. In the event that penicillin related antibiotics do not work in an infection, antibiotics in the quinolone and macrolide families are often used instead. However, as rates of antibiotic resistance rise, scientists are looking for other ways to manage these bacterial infections.

What we can do to prevent H. influenzae infections.

The key to prevention of these infectious diseases is vaccinating people before they are exposed. In the USA, vaccination against H. influenzae type b (Hib) is part of the routine pediatric vaccination schedule. The CDC recommends children to be vaccinated against Hib at 2 months followed by up to 3 boosters within the last 15 months of life. In the US, children older than 18 months began being vaccinated for Hib; shortly after, in 1990, the vaccine was approved for infants, who are most susceptible to Hib infections. Since then, the incidence of Hib infections in children under the age of 5 has decreased by 99%. The vaccine is made with sugars from the capsule of Hib, making the immunity specific only to encapsulated type b strains of H. influenzae, leaving people still susceptible to colonization and infection by non-type b strains as well as unencapsulated strains.