Streptococcus pyogenes

Written for The International Microbiology Literacy Initiative

Claim to fame: medical history “firsts”

Streptococcus pyogenes has been instrumental to our understanding of infectious disease. It was one of the first organisms identified as the cause of contagious diseases, some of the first antibacterial treatments were administered on S. pyogenes infections, and as our understanding of infectious disease grew, hospitals and care facilities developed better hygiene practices resulting in less and less people getting sick from these common bacterial infections.

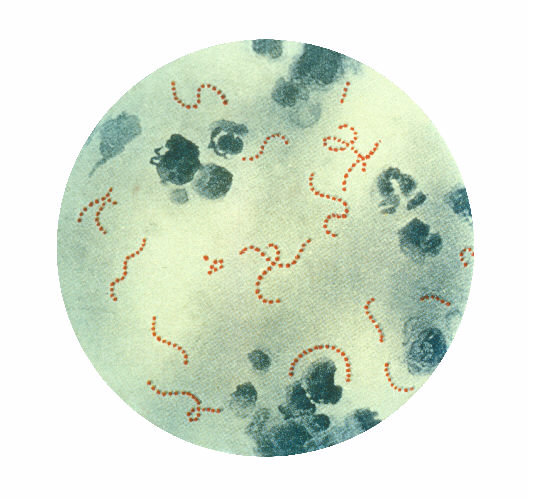

S. pyogenes is the bacteria behind a variety of different human diseases. In 1874, an Austrian surgeon named Theodore Billroth isolated a microbe from patients with skin infections. He described what he saw under the microscope as “small organisms…isolated or arranged in pairs, sometimes in chains of four to twenty or more links” and named them “streptococcus” (strepto- meaning “chain” and coccus meaning “berries” in Greek.) Then in 1884, a German physician and scientist named Friedrich Julius Rosenbach added “pyogenes” to the name after observing the microbe in patients with infections that produced pus (pyo- meaning “pus” and -genes meaning “forming” in Greek.)

Strep Throat (Streptococcal Pharyngitis)

Most of us run into S. pyogenes in the form of strep throat. Signs of strep throat include a sore throat, fever, pus from the tonsils, and enlarged lymph nodes in the neck. Strep throat occurs when S. pyogenes infects the skin inside of the mouth and throat. The bacteria produce proteins on their surface that act almost like Velcro, allowing them to stick to the skin cells that line the mouth and throat. From there, S. pyogenes makes itself at home in the throat by replicating itself, pushing out other harmless species of bacteria, and sometimes even entering the cells in our throat to hide from our immune system.

Scarlet Fever

Once S. pyogenes has found a comfortable spot in our throats, in some infections, the bacteria will start to produce toxins. These toxins cause the characteristic red rash that scarlet fever was named after. Another distinctive feature of scarlet fever is a tongue covered in a white film with red spots giving the appearance of a “white strawberry tongue.” One of the earliest known descriptions of scarlet fever was in 1553 by a Sicilian physician Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia. He described patients who had “numerous spots, large and small, fiery and red…so that the whole body appeared to be on fire,” and called the disease “rossalia.” It wasn’t until 1884 that the German physician Friedrich Loeffler connected the disease to S. pyogenes. Later on, in the 1920s, George and Gladys Dick, both American physicians, discovered that S. pyogenes produced scarlet fever toxin that differentiated scarlet fever from typical strep throat infections.

Skin Infections (Impetigo)

S. pyogenes is also able to infect the skin in the same way they infect the throat. The infection causes red sores that produce pus and fluid that dries, forming a honey-colored scab. While it’s certainly easier for the bacteria to make its way into our cells if the skin is broken, S. pyogenes is able to invade without needing an opening.

Flesh-eating Disease (Necrotizing Fasciitis)

On rare occasion, if a skin infection cannot be cleared by the immune system or through treatment, S. pyogenes can make its way deeper and infect the layers under the skin. S. pyogenes burrows under the skin into the layers of connective tissue that separate the skin and muscle and eats away at the soft tissue. This particular infection advances very quickly, making it very important to identify it early. If left untreated, proteins made by the bacteria can overstimulate the immune system causing toxic shock syndrome, which is often life threatening. Depending on how severe the infection is, this disease is usually treated by surgically cutting out the infected flesh. Some severe cases may require amputation.

Transmission

S. pyogenes only naturally infects humans, which means the only way to catch S. pyogenes related diseases is from other humans. A person with strep throat can spread S. pyogenes through respiratory droplets when coughing or sneezing. Those respiratory droplets can land on the skin of other people, causing impetigo, or be breathed in, causing strep throat or scarlet fever. Someone with a skin infection can also spread S. pyogenes through scratching their infections and coming in to contact with other people. Outbreaks of S. pyogenes related diseases are more common in crowded spaces like schools, nursing facilities, and military camps.

Treatment and Prevention

Many mild cases of strep throat and impetigo resolve on their own without treatment. However, treatment with antibiotics can lessen symptoms and shorten the course of the infection, which helps curb spread. S. pyogenes is particularly sensitive to penicillin, making it the antibiotic of choice for most infections. Penicillin can be given either orally in a pill format, or topically for cases of impetigo. Recently, researchers have found some strains of S. pyogenes that sport a rare mutation making them more resistant to penicillin treatment. The concerning rise of antibiotic resistance means that researchers are looking for other ways to prevent S. pyogenes infections. There aren’t any vaccines for S. pyogenes currently, but researchers are on the hunt for proteins that can train our immune systems to identify and attack S. pyogenes before it is able to establish an infection.

What we can do to prevent S. pyogenes infections.

Since S. pyogenes is spread from person to person, all the methods to prevent disease transmission involves avoiding contact with infected individuals. An infected individual can reduce spread through respiratory droplets by wearing a mask and avoiding touching and scratching skin lesions. Hand washing will also prevent skin infections, and keeping cuts and broken skin clean and covered lowers the chances of S. pyogenes finding and establishing a home in your skin.